[ad_1]

When Eric Mueller, who was adopted, first observed a photograph of his start mother, he was get over by how alike their faces were being. It was, he wrote, “the very first time I ever observed another person who looked like me.” The encounter led Mueller, a photographer in Minneapolis, into a a few-12 months challenge to photograph hundreds of sets of related people today, culminating in the book Family Resemblance.

These kinds of resemblances are commonplace, of class — and they place to a sturdy underlying genetic impact on the face. But the closer researchers look into the genetics of facial attributes, the a lot more advanced the picture gets. Hundreds, if not 1000’s, of genes have an impact on the shape of the encounter, in mostly refined approaches that make it almost difficult to predict a person’s face from examining the impact of each gene in change.

As researchers master extra, some are starting to conclude that they require to look in other places to produce an comprehending of faces. “Maybe we’re chasing the completely wrong factor when we’re hoping to develop gene-degree explanations,” states Benedikt Hallgrímsson, a developmental geneticist and evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Calgary, Canada.

Rather, Hallgrímsson and other people consider they may well be ready to group genes into groups that get the job done together as the confront kinds. Comprehension how these teams perform, and the developmental processes they have an affect on, must be substantially extra workable than attempting to type out the effects of hundreds of unique genes. If they’re proper, faces might flip out to be significantly less complex than we consider.

Plotting the facial landscape

When geneticists first set out to recognize faces, they started off with the minimal-hanging fruit: determining the genes dependable for facial abnormalities. In the 1990s, for example, they acquired that a mutation in 1 gene causes Crouzon syndrome — characterized by huge-set, often bulging eyes and an underdeveloped upper jaw — although a mutation in a diverse gene potential customers to the down-slanting eyes, tiny reduced jaw and cleft palate of Treacher Collins syndrome. It was a begin, but these kinds of serious conditions said little about why usual faces range as much as they do.

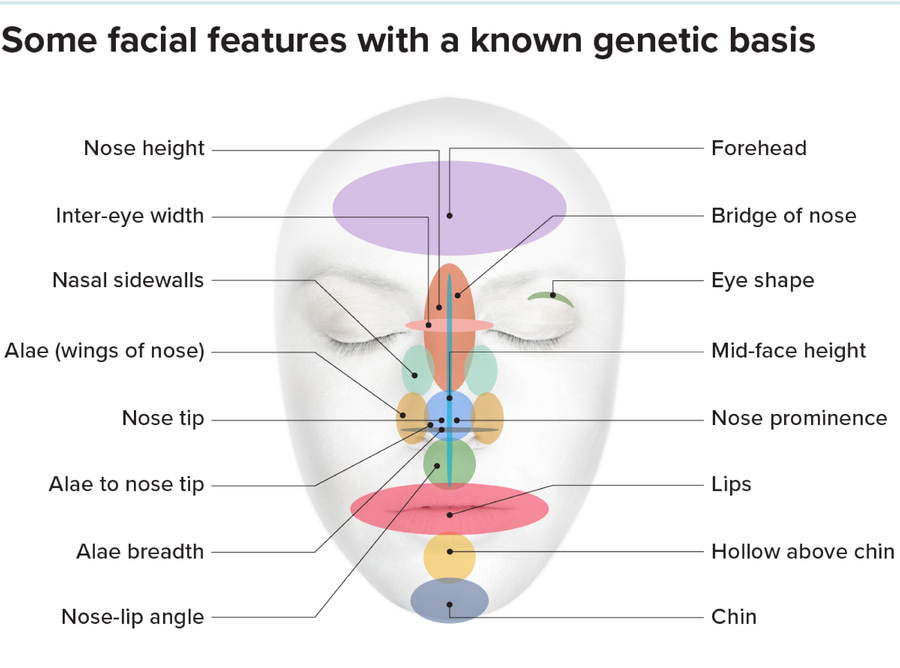

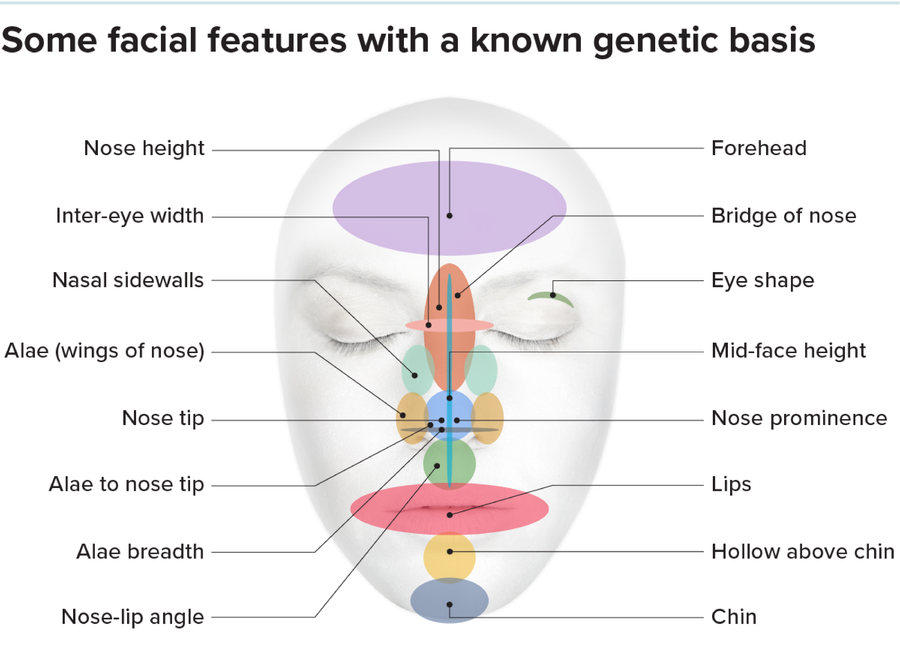

Then, commencing about a decade in the past, geneticists commenced to choose a different approach. Initially, they quantified countless numbers of typical faces by pinpointing landmarks on just about every person’s experience — tip of chin, corners of lips, idea of nose, outside the house corner of just about every eye, and so forth — and measuring the distances amongst them. Then they screened the genomes of those people people, to see regardless of whether any genetic variants corresponded with specific facial measurements, an analysis acknowledged as a genome-huge association research, or GWAS (pronounced jee-wass).

Some 25 GWASs of facial form have been published to date, with above 300 genes recognized in total. “Every single location is spelled out by numerous genes,” says Seth Weinberg, a craniofacial geneticist at the College of Pittsburgh. “There’s some genes pushing outward and many others pushing inward. It is the whole stability that ends up turning out to be you, and what you glance like.”

Not only are there a slew of genes included in each certain facial region, the variants uncovered thus much never account effectively for the details of just about every facial area. In a study of the genetics of faces in the 2022 Once-a-year Evaluation of Genomics and Human Genetics, Weinberg and his colleagues collected GWAS final results on the faces of 4,680 folks of European ancestry. Regarded genetic variants described only about 14 % of the dissimilarities in faces. An individual’s age accounted for 7 per cent, sexual intercourse for 12 p.c, and body mass index for about 19 p.c of variation, leaving a whopping 48 percent entirely unexplained.

Clearly, something significant in figuring out the form of faces isn’t captured by GWASs. Of class, some part of that missing variation should be stated by surroundings — in truth, scientists have noted that sure components of the confront, including the cheeks, decrease jaw and mouth, do seem to be much more vulnerable to environmental influences this sort of as food plan, ageing and local weather. But an additional clue to that missing variable, numerous researchers agree, lies in just the special genetics of person people.

Variants excellent and tiny

If faces had been simply just the sum of hundreds of little genetic effects, as the GWAS effects indicate, then every single child’s face must be a ideal blend, midway between its two moms and dads, Hallgrímsson suggests, for the identical motive that flipping a coin 300 situations will pretty much often generate around 150 heads. Nonetheless you only have to appear at particular households to see which is not the scenario. “My son has his grandmother’s nose,” claims Hallgrímsson. “That must imply there are genetic variants that have huge results in just households.”

But if some face genes do have huge effects that are noticeable in the family members that have them, why really don’t they show up in a GWAS? Maybe the variants are much too scarce in the common populace. “Facial shape is genuinely a mixture of common and scarce variation,” says Peter Claes, an imaging geneticist at KU Leuven in Belgium. As a possible illustration, he factors to French actor Gérard Depardieu’s unique nose. “You do not know the genetics yet, but you come to feel this is a rare variant,” he states.

A few other distinct facial features that run in families, these kinds of as dimples, cleft chins and unibrows, could also be candidates for such uncommon, superior-influence variants, says Stephen Richmond, an orthodontic researcher at the College of Cardiff, Wales, who scientific studies facial genetics. To appear for this kind of exceptional variants, although, scientists will require to go outside of GWASs to investigate substantial datasets of total-genome sequences — a task that will have to wait until finally these types of sequences, connected to facial measurements, turn out to be a great deal much more plentiful, claims Claes.

A further risk is that the similar gene variants that have tiny results most of the time could have larger sized outcomes within selected people. Hallgrímsson has observed this in mice: He and his colleagues, notably Christopher Percival, now at Stony Brook University, launched mutations that have an affect on craniofacial shape into a few inbred lineages of mice. They learned that the 3 lineages finished up with quite distinct facial styles. “The same mutation in a distinct pressure of mice can have a various influence, sometimes even the reverse effect,” suggests Hallgrímsson.

If a thing related transpires in individuals, it is feasible that within a individual family members — as with a distinct pressure of mice — the family’s distinctive genetic background may make sure experience shape variants more strong. But proving that this happens in persons, without the assist of inbred strains, is most likely to be tricky, Hallgrímsson claims.

A far better technique, Hallgrímsson thinks, may well be to seem at the developmental processes that underlie how faces are formed. Developmental procedures require teams of genes that work with each other — often to regulate the activity of nevertheless other genes — to handle how unique organs and tissues sort for the duration of embryonic enhancement. To determine processes linked to deal with form, Hallgrímsson and his workforce to start with used extravagant figures to find genes that influence craniofacial variation in more than 1,100 mice. Then they turned to genetics databases to establish the developmental procedures that every gene was a portion of. The assessment flagged 3 procedures as specially essential: cartilage improvement, brain progress and bone formation. It’s feasible, Hallgrímsson speculates, that specific variances in the amount and timing of these three processes (and probably some other individuals) could be a big section of the clarification for why a single person’s confront differs from another’s.

Intriguingly, it appears that some of these groups of genes may have “captains” that direct the action of other group members. Researchers making an attempt to have an understanding of facial variation might as a result be capable to emphasis on the motion of these captain genes alternatively than hundreds of unique genetic players. Help for this notion will come from an intriguing new review by Sahin Naqvi, a geneticist at Stanford University, and his colleagues.

Naqvi started with a paradox. He understood that most developmental processes are so finely tuned that even modest adjustments in the action of the genes regulating them can cause severe developmental difficulties. But he also realized that tiny dissimilarities in those people incredibly exact same genes are probable the motive his have experience seems distinct from his neighbor’s. How, Naqvi questioned, could the two of these suggestions be legitimate?

To try out to reconcile these two contradictory notions, Naqvi and his colleagues decided to target on one regulatory gene, SOX9, which controls the exercise of quite a few other genes included in the advancement of cartilage and other tissues. If a human being has only just one doing the job duplicate of SOX9, the consequence is a craniofacial ailment identified as Pierre Robin sequence, characterised by an underdeveloped decrease jaw and various other difficulties.

Naqvi’s team set out to reduce SOX9 activity little by tiny and evaluate what effect that had on the genes it regulates. To do so, they genetically engineered human embryonic cells so that they could dial down SOX9’s regulatory action at will. Then the researchers calculated the effect of six different SOX9 levels on the exercise of the other genes. Would the genes under SOX9’s regulate keep their activity inspite of smaller improvements in SOX9, thus trying to keep enhancement steady, or would their action drop in proportion to changes in SOX9?

The genes fell into two classes, the workforce observed. Most of them didn’t adjust their action unless SOX9 levels fell to 20 p.c or much less of standard. That is, they appeared to be buffered towards even rather big modifications in SOX9. This buffering — quite possibly the end result of other regulatory genes compensating for reductions in SOX9 — would aid hold improvement finely tuned.

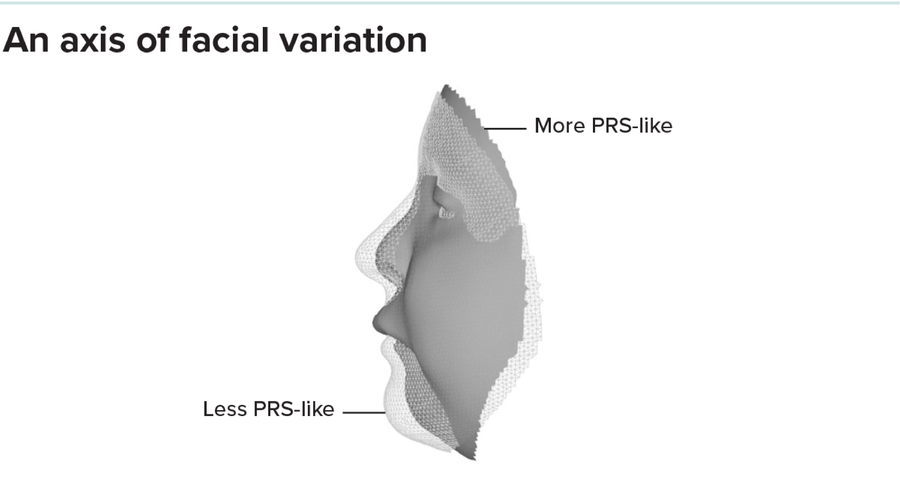

But a smaller subset of the genes turned out to be delicate to even little modifications in SOX9, dialing their possess activity up or down in lockstep with it. And those people genes, the researchers identified, tended to have an effect on jaw dimensions and other facial features altered in Pierre Robin sequence. In reality, these unbuffered genes seem to figure out how significantly, or how minor, a common face resembles a Pierre Robin just one. At a person end of the array lie the underdeveloped jaw and other structural variations of Pierre Robin sequence. And at the other stop? “You can think of the anti-Pierre Robin as an overdeveloped jaw, elongated with a outstanding chin — type of like me, actually,” suggests Naqvi.

In essence, SOX9 captains a staff of genes that outline 1 direction, or axis, in which faces can vary: from additional to significantly less Pierre-Robin-like. Naqvi is now on the lookout to see no matter if other teams of genes, every single captained by a distinctive regulatory gene, define more axes of variation. He suspects, for illustration, that genes sensitive to tiny changes in a gene called PAX3 might define an axis relating to the form of the nose and brow, when all those delicate to yet another called TWIST1 — which, when mutated, leads to premature fusing of the skull bones — could determine an axis relating to how elongated the cranium and forehead are.

Other proof hints that Naqvi may be on the suitable monitor in imagining that faces vary together predefined axes. For illustration, geneticist Hanne Hoskens, Claes’s former student and now a postdoc in Hallgrímsson’s lab, sorted people’s faces in accordance to how carefully they resembled the prominent forehead, flattened nose and other characteristics attribute of achondroplasia, the most popular sort of dwarfism. (Believe of the actor Peter Dinklage, for case in point.) These at the far more dwarflike finish of the array tended to have unique variants of genes connected to cartilage advancement than all those with significantly less dwarflike faces, she identified.

If comparable styles arise for other developmental pathways, this may well established guardrails that prohibit the way faces create. That could aid geneticists lower through the complexities to extract broader ideas underlying facial form. “There is a limited set of directions along which faces can fluctuate,” suggests Hallgrímsson. “There are plenty of directions that there is a incredible volume of variation, but it is a small subset of the geometric alternatives we see. And it is due to the fact these axes are identified by developmental processes, and there are fairly handful of developmental processes.”

Till a lot more benefits are in, it is also early to say no matter whether this new solution truly holds an important critical to detailing why just one person’s face seems different from another’s — and the shock of recognition Eric Mueller experienced when he noticed his mother’s image for the first time. But if Hallgrímsson, Naqvi and their colleagues are on the ideal observe, concentrating on developmental pathways may perhaps give a way to section the thicket of hundreds of genes that for so lengthy has obscured our knowledge of faces.

This report initially appeared in Knowable Magazine, an impartial journalistic endeavor from Annual Evaluations. Indicator up for the publication.

[ad_2]

Supply link