[ad_1]

Black men and women face some of the maximum cancer and bronchial asthma costs in the U.S., data that are inarguably connected to the atmosphere in which an individual life, performs and plays. But till Robert D. Bullard began gathering data in the 1970s, no one particular thoroughly understood how a person’s surroundings can have an effect on their wellness. And no a single, not even Bullard, knew how segregated the most polluted areas actually ended up.

Bullard was the initial scientist to publish systematic analysis on the one-way links in between race and exposure to pollution, which he documented for a 1979 lawsuit. “This is just before every person experienced [geographic information system] mapping, prior to iPads, iPhones, laptops, Google,” he states. “This is undertaking analysis way back again with a hammer and a chisel.”

In 2021 Texas Southern College in Houston established the Robert D. Bullard Heart for Environmental and Local weather Justice, where Bullard now serves as government director. He has created 18 textbooks on the subject matter, and his work assisted to start a movement. Environmental justice—the thought that everyone has the ideal to a clear and balanced environment, no make any difference their race or class—has been embraced by advocates all-around the earth and is influencing intercontinental climate negotiations. Scientific American requested Bullard about his work and its impression in the U.S. and beyond.

https://www.youtube.com/view?v=5Ol_Zh7Qg4A

An edited variation of the interview follows.

Your early work signaled the commence of a new field. How would you explain it?

I do what is actually called “kickass sociology.” I have tried out to pattern my work following a kickass Black sociologist: W.E.B. DuBois, who confirmed how an individual can be a trainer, scholar, researcher, writer, social critic and activist. He served to discovered the NAACP [in 1909]—the oldest and most significant civil rights firm in the U.S.—and he did some of the initial empirical study in sociology.

Your initial paper, in 1979, was the 1st to use hard info to quantify environmental racism. What prompted you to appear into this?

The analyze was performed in support of Bean v. Southwestern Squander Management Company, the initially U.S. lawsuit to obstacle environmental racism applying civil rights regulation. The law firm for that scenario was Linda McKeever Bullard, my spouse at the time, and she necessary numbers to back up the argument that locating strong squander landfills in a distinct community was a kind of discrimination. The neighborhood was middle course, suburban and an not likely location for a rubbish dump. It was also predominantly Black.

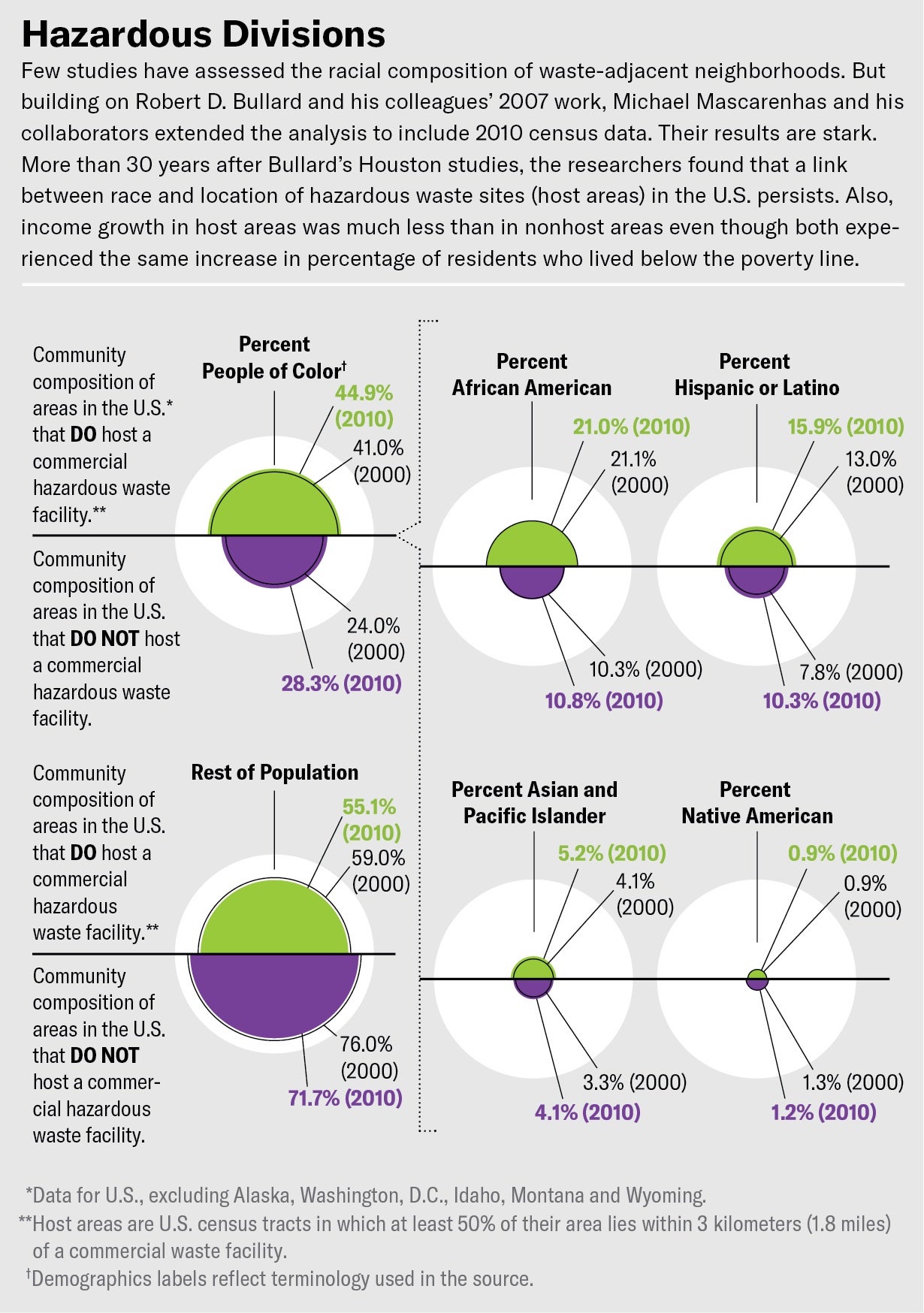

My position was to style the examine, collect the data, and existing maps that showed the place all the landfills, incinerators and reliable waste internet sites had been positioned in Houston from the 1920s up to 1979. We uncovered that five out of 5 of the metropolis-owned landfills had been in predominantly Black neighborhoods, as were a few out of 4 of the privately owned landfills. Six out of 8 of the city’s incinerators were being in Black neighborhoods. Black men and women designed up only 25 percent of Houston’s inhabitants at the time, but 82 p.c of the garbage in the metropolis was dumped on them.

We shed in court due to the fact we could not show it was intentional discrimination. It was less difficult to show scientifically that this pattern reflected a kind of discrimination and not random data, but it can be a lot more difficult to confirm it in court.

When you saw how prevalent this air pollution was in Black communities, what did you think?

I was stunned. I was surprised and shocked. But I was even more surprised and shocked and unhappy that the judge failed to see it. This was 40-something years in the past. The judge was an outdated white person who was contacting Black plaintiffs in the case “Negresses.” That is a fancy, dressed-up way of calling you the N-phrase. The racial undertone was so thick. It was pretty much as if that scenario have been brought too soon.

What was the general public response to your first studies?

Communities on the floor, the ones who have been staying poisoned and disregarded, started out to come alongside one another. Grassroots and civil legal rights groups began to develop coalitions and collaborate. By 1990 we have been arranging the Initial Nationwide Folks of Shade Environmental Leadership Summit. The field attacked us. Some of us were being sued. Some of us were intimidated and threatened. But we have saved combating since we have justice on our aspect. A good deal of men and women attempted to debunk our work, but they in no way could. We experienced to struggle with some of our environmental allies: conservation teams that had been mainly white and affluent. They’re with us now, but they have been not constantly.

How have you designed on those first experiments?

I expanded my Houston research. I preferred to know regardless of whether the Houston example was an outlier. That is how the to start with reserve on environmental justice arrived about. I wrote Dumping in Dixie in 1989, but it took me a 12 months to get that book printed. I experienced crystal clear details demonstrating that this discrimination was occurring from Houston to Dallas, to the Louisiana Most cancers Alley, to the Alabama Black Belt, to West Virginia. But the publishers stated, “There’s no these thing as environmental injustice. All people is dealt with the very same. The setting is neutral.”

All of what we’ve carried out since the Houston review has intentionally challenged the dominant paradigm. We argue that communities that have in some way been still left out and left behind really should be first in line when we converse about protection. Rules should really safeguard the most susceptible populations, especially young children of color.

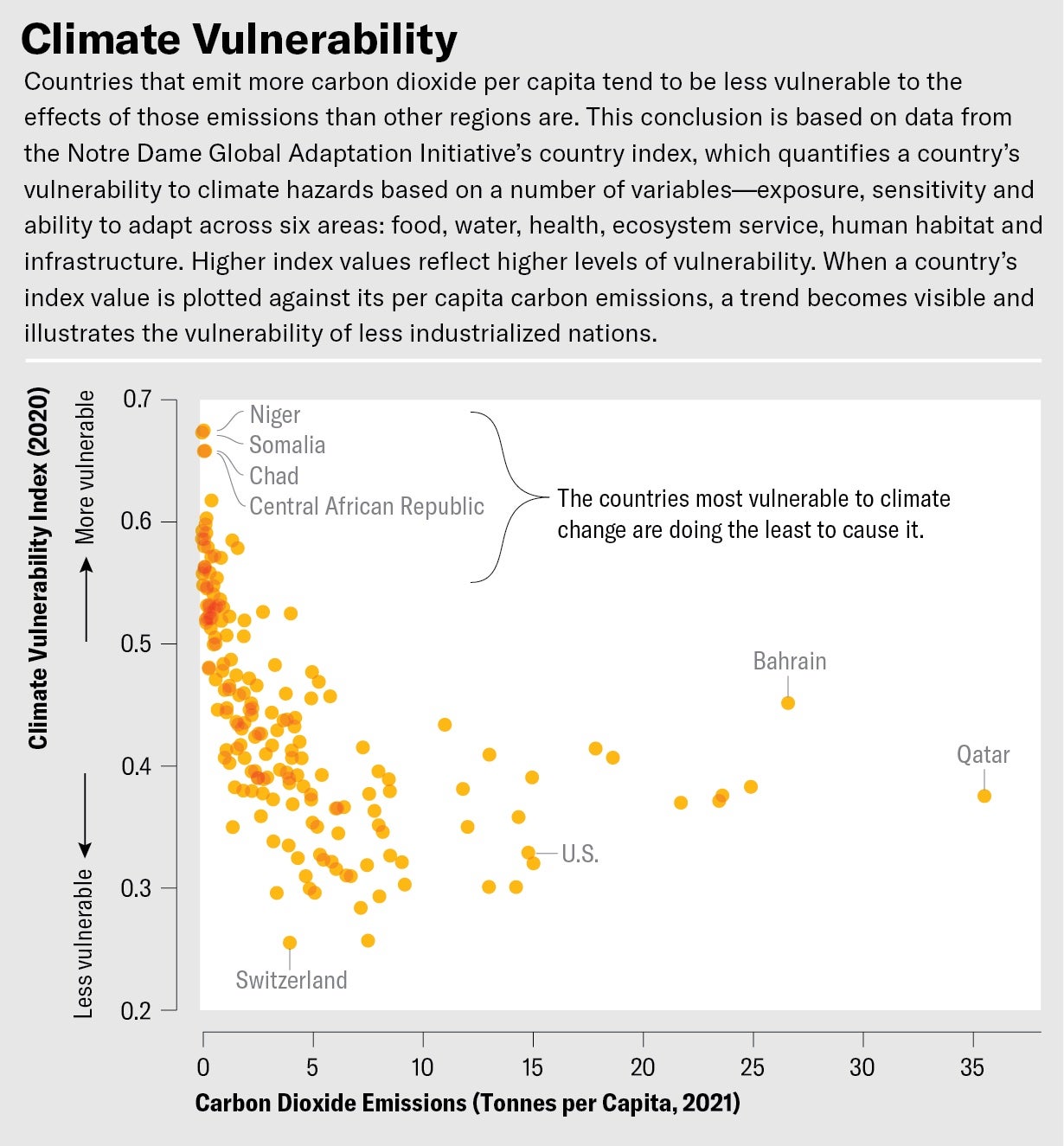

Now environmental justice is not just in the U.S. It is international. It has been adopted into environmental reparations endeavours. We communicate about generating our communities whole mainly because of the hurt the fossil-gas field has induced. We speak about repairing our communities. In a worldwide sense, reparations have translated into the Reduction and Damage Fund, a pot of income founded by better-earnings nations around the world at the 2022 United Nations Local weather Change Conference. The fund aims to mitigate hurt extra created international locations have brought on in significantly less developed nations, which have contributed the the very least to local climate modify. They’re emotion the suffering and struggling very first, worst and longest. It took 27 local weather summits ahead of the Reduction and Damage Fund was adopted as a policy.

The road to the place we are now has not been a mattress of roses. We have usually had detractors and people who have been effectively funded in fights towards us.

What about world environmental racism and the value of working with a global lens?

We held our Initial National Men and women of Colour Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991, and reps attended from the broad bulk of U.S. states, as well as various overseas countries and tribal nations. Our ideas of environmental justice—which consist of the safety of staff, the legal rights of Indigenous peoples and the honoring of nature—have been translated into 50 percent a dozen languages. And globally, in nations around the world that have experienced since of colonialism, imperialism and racism, communities are now applying that exact environmental justice lens to their organizing. Our principles of environmental justice resonated with the World wide South. Those nations around the world that have contributed the the very least to weather adjust are emotion that ache and struggling ideal now, as they have been for a long time.

The environmental and local climate justice framework that we use for the investigate in the U.S. has expanded to universities across the globe: South Africa, Australia, Scotland. In some situations, they use not a racial lens but an equity lens that looks at gender, income, former colonization position, and market forces that have stripped persons of the energy to come to a decision for on their own irrespective of whether they want a new venture in their communities.

This investigation is supported by the framework that we set in location, one that employs a neighborhood-college partnership. The men and women who are most negatively impacted also have awareness and methods. These conclusions have an affect on their homes, their families and their life, so it can be essential that they continue being concerned. Community science is in all probability the swiftest-escalating portion of the worldwide local weather and environmental justice movement.

How did race come to be this sort of a defining variable in the U.S. for who receives clear air or h2o and who does not?

Racism is deeply ingrained in America’s DNA. Race has often played a significant component in who’s no cost, who receives educated and who is a citizen. There was slavery, then emancipation and Jim Crow segregation, wherever “separate but equal” was codified. If a Black individual, for example, compensated the exact same taxes as a white person, all those taxes had been not put in in a way that gave them equivalent safety and treatment method.

The Civil Legal rights Act was wasn’t handed until eventually 1964. Racial redlining drew a line around Black and brown neighborhoods, labeling them as harmful and undesirable for financial loans. That prevented our neighborhoods from benefiting from infrastructure this sort of as sewer and water techniques.

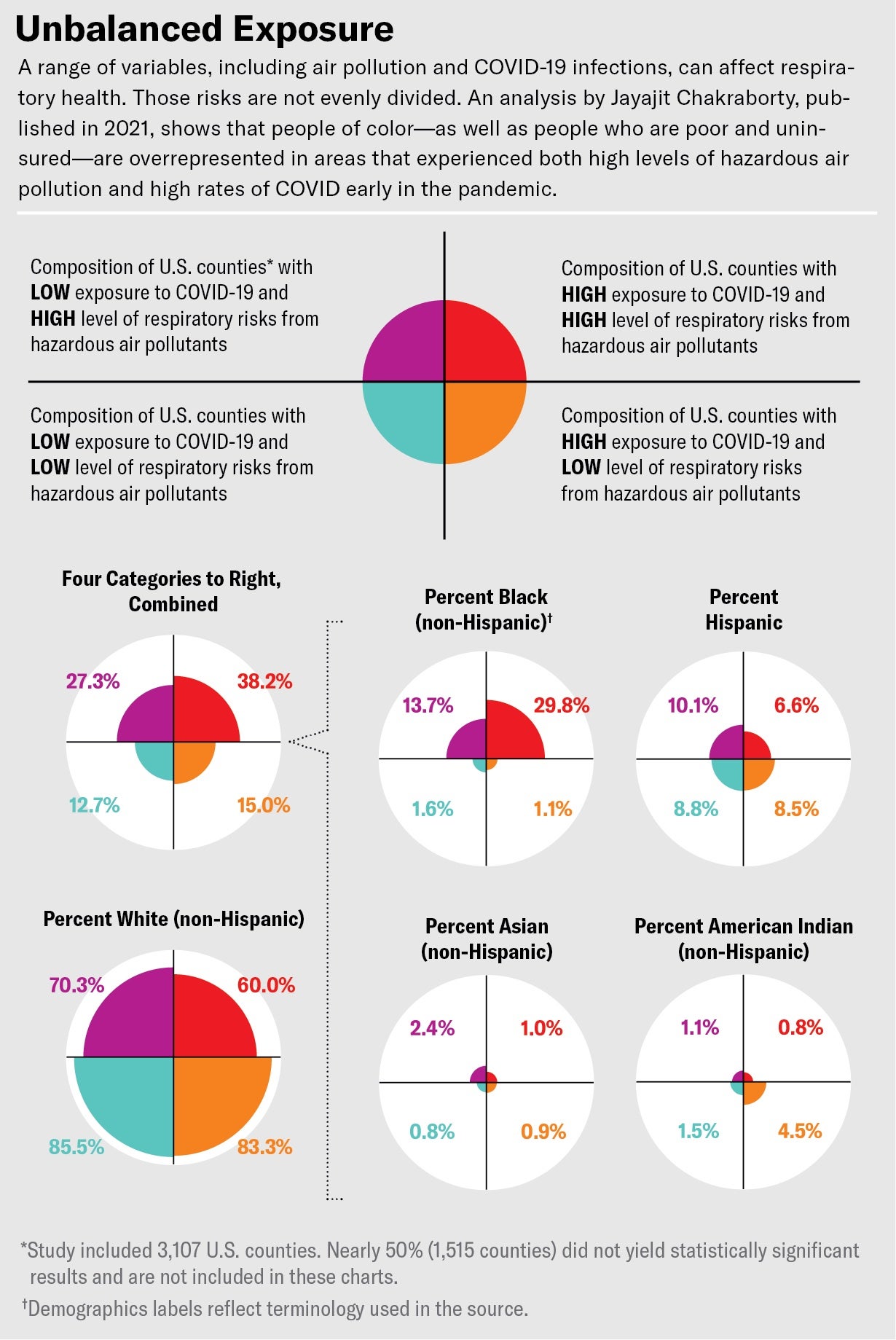

We are now viewing the legacies of that racism. Neighborhoods that were redlined 100 years ago are hotter these days mainly because of city heat islands [see Islands of Illness]. They have no tree cover or parks or inexperienced place. They’re more inclined to flooding because they absence flood security. They are far more vulnerable to industrial pollution. And we have realized that the exact same neighborhoods were more vulnerable to COVID hospitalizations and fatalities.

These are all illustrations of how previous racism retains having transferred ahead: it boosts vulnerability.

You’ve got been performing this for just about 50 several years now. What keeps you likely?

I have witnessed environmental justice go from a footnote to a headline, which signifies we are creating inroads and development in research and in plan. Even although we have produced strides, we have a extended way to go. Just owning the details has in no way been ample. We have to acquire these conclusions and convert them to coverage. You have to marry information with motion, and you will find not been ample action—even soon after all the reams and reams of research.

What comes up coming for you?

We have a pair of tasks. A person is our participation in the U.S. government’s Justice40 Initiative, which is funded by the Bezos Earth Fund. It appears to be at how our heart can do the job with communities and use our HBCU [historically Black college or university] consortium to support communities that have been underserved and invisible when it comes to issues all over climate, economic growth, housing, transportation and thoroughly clean electrical power.

One more is a Bloomberg challenge we’re participating in that looks outside of petrochemicals. How do we explore transitioning to a clean electrical power financial system and, at the exact same time, make sure that transition is equitable, reasonable and just?

We are supporting community-based companies in Texas resist the 80-moreover new oil and fuel amenities proposed for Houston, Beaumont-Port Arthur and Corpus Christi—areas by now impacted by petrochemical plants. This is complemented by a research we’re carrying out that examines the environmental justice implications of swift permitting and establish-out of terminals for liquefied natural fuel in the Gulf Coast. Ironically, quite a few of the new services are being proposed in communities in which most inhabitants have small incomes or are individuals of colour and where by they are by now burdened with petrochemical vegetation.

We’re also wanting at the Inflation Reduction Act and the extent to which our heart can collaborate with other organizations to make sure a holistic tactic when we talk about greenhouse gasoline reduction. When we converse about slicing emissions, we’re also speaking about creating inexperienced work and about supporting smaller-enterprise entrepreneurs so they can be resourceful and revolutionary. It is really about getting a lot more of our young individuals of coloration interested in science, know-how and engineering so we can build out a pipeline for the potential.

The environmental and local weather justice motion now is intergenerational, and that’s interesting. I have been accomplishing this for 40-in addition years. I’m a Boomer and proud of it—still combating and still standing. But the point is, Millennials and Zoomers and Gen Xers merged outnumber my era. We need to have to develop a robust intergenerational partnership so these youthful men and women you should not have to hit brick partitions.

We will get to the level wherever we will deal with all these problems we have confronted. Many are synthetic boundaries that we can crack down to transfer more promptly towards solutions. We can just take this quest for justice and go the baton. Which is how we will cross the complete line.

[ad_2]

Source connection