[ad_1]

December 1, 2023

2 min study

A chunk of a Mesopotamian palace discovered genes from dozens of historical crops

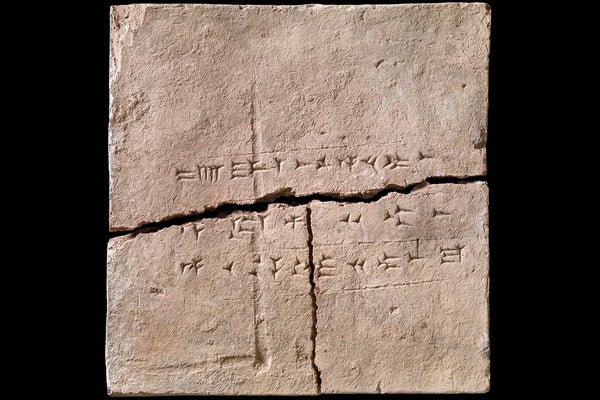

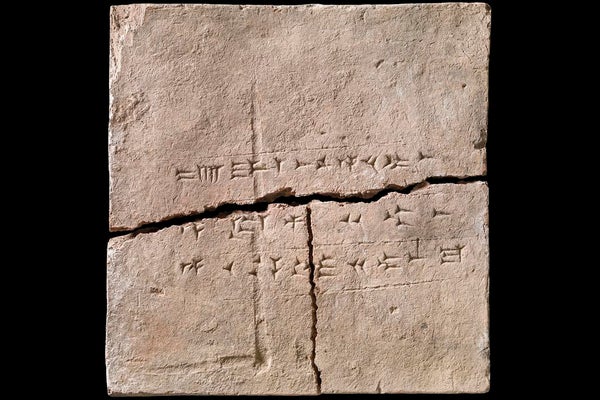

A clay brick from the Nationwide Museum of Denmark from which historical DNA samples were being derived.

Countless numbers of years ago men and women constructing a palace molded mud from beside the Tigris River into a brick, scooping up components of nearby crops in the approach. Scientists not long ago managed to tease discernible plant DNA from that brick, supplying a rare seem at what was increasing in Mesopotamia (now aspect of Iraq) nearly 3 millennia ago, in accordance to a study printed in Scientific Reviews.

“We had been surprised when it turned out that we were being essentially in a position to extract historical DNA from this clay materials,” suggests co-writer Sophie Lund Rasmussen, a biologist at Denmark’s Aalborg University. “This paper is primarily a evidence of strategy we required to share the plan and the method with the environment.”

Even though experts have extracted historical DNA, or aDNA, from bones and lake sediments prior to, they hadn’t imagined to attempt the current tactics on clay bricks. Quite a few bricks utilized to develop historic constructions really don’t have plenty of DNA for scientists to sequence, and bricks are often baked at significant temperatures, which can degrade any plant DNA they may well comprise.

The newly analyzed brick, at the moment held by the Countrywide Museum of Denmark, had been sunshine-dried as a substitute of fired. It was designed amongst 883 and 859 B.C.E. and bears an inscription in the extinct Akkadian language examining “the assets of the palace of Ashurnasirpal, King of Assyria.” A crack in the center of the brick permitted researchers to consider small, far better-preserved samples from deep inside of.

The researchers sequenced the plant aDNA in the brick and identified evidence of 34 taxonomic teams, which includes cabbage, heather, birch and cultivated grasses—new clues as to what people in this “cradle of civilization” eaten. More substantial aDNA fragments, along with innovations in DNA sequencing and device studying (employed to help interpret sequences), could let researchers to detect unique plant species.

“Now the actual do the job starts off, and we have to establish the process further and make it even a lot more precise,” Rasmussen says. Her team’s endeavours exhibit how aDNA can be found in products not commonly considered to include sufficient genetic substance to sequence, she claims.

Ancient DNA sequencing could be utilised with other tactics for examining plant substance to paint a fuller picture of the past, says Mads Bakken Thastrup, an archaeobotanist at Denmark’s Moesgaard Museum, who was not included in the new review. Archaeobotanists now study proof of ancient plant life by employing chemical processes or imaging microscopes extracting aDNA “could potentially be a useful addition,” Thastrup claims. “The findings are nevertheless a little bit ‘low resolution,’ and the approach will most likely need to have even further improvement before we can detect the plants at the species stage. When that turns into feasible, it will be actually exciting.”

[ad_2]

Resource backlink

![Stealth Mode: How to Hide Contacts on iPhone [2024]](https://adultserviceau.com.au/blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/how-to-hide-contacts-on-your-iphone-150x150.jpg)